As the season winds down, we have a period of contemplation – both as coaches and athletes – when we look back at the season and consider the good and the bad, what worked and what didn’t, and what we want from the coming season. During this time, I always come back to “why coaching?” I look at this question both from a coach’s perspective and an athlete’s perspective as I currently have the opportunity to participate in our sport under both of those titles.

This year, I dug a bit deeper into the topic, and I’m sharing my thoughts here in the hope that they will inform and inspire other athletes and coaches to always be moving forward in their approach to the sport and its corresponding lifestyle. It is important to note that my thoughts here are representative of coaching as I feel it should be. As most of us know, it is not always as pictured below. There are a wide range of individuals operating under the title of “coach,” and athletes’ experiences with these professionals vary widely. However, this is not intended to be an attack on any coaches that may be struggling to fulfill these objectives – rather, it is intended to encourage those that identify a lack to endeavor to fill it. If you are an athlete, and you do not see the following in your coach/athlete relationship, schedule time to speak with your coach about expectations, rather than abandon ship – switching coaches brings its own set of challenges. If you are a coach and you do not see the following in your coach/athlete relationship, make plans to address this need – while coach education may sometimes seem thin on the ground, legitimate coaches and programs do exist that will work with you to help you reach your potential. None of us would be where we are without the mentors who have guided us there.

So without further ado – why coaching?

1. Coaching provides effective analysis and planning of training load. Every coach/coaching group should have a proven method of calculating and planning overall training load (the combined stress on the body of all training activities), and an approach to applying both stress and recovery in effective cycles. Let me briefly break this down in case this sounds like Greek to anyone reading.

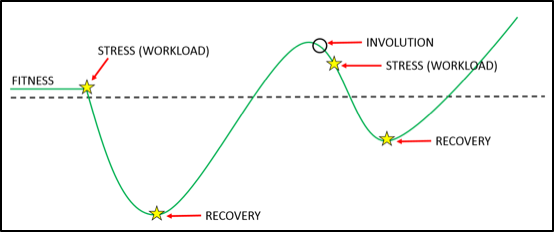

Any attempt to gain fitness ultimately is built on the concept of the supercompensation cycle, which is a long phrase that essentially theorizes the following:

The above visual, in essence, says that when we apply training stress to an athlete, their fitness initially decreases (recall how you feel immediately after hard training – somewhat beat up and fatigued, right?), but upon application of recovery methods, fitness not only returns to baseline, but increases to be better prepared to meet that specific stress in future. Eventually, if stress is not applied again, involution occurs and fitness begins to decrease once more. Balancing these ups and downs is one of the core jobs of any coach.

Many coaches use the TrainingPeaks Total Stress Score (TSS) in their planning. Here at Playtri, we have a similar proprietary method that we have proven over and over again as effective for triathlon (it is also proving to be effective for single sport, but we have less data to base this claim on), and feel confident in recommending to potential athletes. Regardless of the approach, this is a data-based analysis that provides an objective look at the athlete’s progress or lack thereof, and data-based solutions. This should lead to increased confidence in achieving goals, and decreased likelihood of illness, injury and burnout.

2. Coaching provides objectivity. Following up on our previous point, coaches have the ability to provide an objective analysis of an athlete’s past, present and future progress. This is perhaps one of the greatest benefits of having a coach, as regardless of our individual knowledge as athletes, it is extremely difficult to view our own progress objectively. Emotional reactions to the physical reactions during training and racing (and even during the off-hours) are normal and will never be entirely preventable, which makes keeping an eye on the bigger picture very challenging. This is why, as an athlete, I always work with a separate coach when I am doing structured training. The ability to see the workout, complete the workout regardless of feel, and then essentially move on from the workout (particularly if it didn’t “feel” the way I wanted), is a valuable thing.

3. Coaching provides a training plan that is effective for the individual athlete. This is the primary reason you will hear many coaches decrying what is known as “pre-fab” training plans, because we see that these plans’ ability to create improvement is vastly limited by their lack of attention to the intricacies (current fitness level/schedule/outside commitments/mental and emotional condition) of the individual athlete. We’ve probably seen a lot of athletes either get injured or fail to reach their goals in attempting to follow these plans. A large part of a coach’s job is to provide the load and goal-specific fitness the athlete requires, within a schedule that is both possible and sustainable for the individual athlete. What if athletic history and availability for training indicates the athlete isn’t capable of the load required for the proposed goal? In this case, it is the coach’s job to provide the athlete with an honest assessment of this fact, and potentially recommend either a different goal, or a different timeline.

One challenge I have run into on this front is coaching in the team environment with daily team sessions – it has to be said that it can make it more challenging to address individual needs, but of course the counter-argument is that it allows the coach to have eyes on the athletes, and it provides the athlete with added motivation in the form of teammates to push and encourage them during tough sessions.

A brief note on this topic for athletes: Athletes with aggressive goals and/or limited flexibility in training availability should anticipate paying more for this benefit as the coach will be required to make more adjustments throughout not just the season, but on a weekly and sometimes daily basis, as well as needing to spend additional time prescribing daily recovery techniques, nutrition, hydration, hours of sleep, etc. to ensure the athlete can quickly and effectively recover from a higher level of stress. I have found with some athletes – even utilizing a very efficient system and almost a decade of experience – that I can spend 5-7 hours a week making these adjustments for a single athlete. That can add up to 20-28 hours a month if you do the math, and if you consider a typical entry-level coaching coast of about $150/month, that is $5.35 to $7.50/hour just for weekly adjustments (not including adjustments/updates to the macro plan throughout the month), which of course is not sustainable.

4. Coaching identifies and makes plans to efficiently correct key weaknesses. Coaches, through experience and education, have the knowledge to identify weaknesses that may limit and athlete in his/her ability to reach a specific goal. Specific weaknesses may be more or less important to specific goals – this is very important! Spend too much time identifying and addressing a secondary limiter to the detriment of a key limiter and it can sabotage the athlete’s ability to achieve the goal. It is impossible to correct every weakness in a single season, so selecting the proper areas to focus on is a crucial part of the coach’s role.

5. Coaching helps the athlete stay in the budget. What? Yes. A large part of the triathlon coach’s role is guiding the athlete in the purchase and use of equipment and other resources. The list of things you can spend money on in this sport is endless (gear, performance testing, travel, races, nutrition, computerized bike fits, etc.), and it is very easy to waste valuable resources on a “cool” or “trendy” item, only to learn it is either not relevant, poorly researched/executed, or not key to the athlete’s primary goal(s).

Coaches – you must know what is out there and how beneficial it is (or isn’t) to your athletes and their individual goals. I have met coaches who think that the retail portion of the sport is “below” them – this could not be further from the truth. The purchases your athlete makes directly impact their ability to perform, as well as their budget for other items that may be more helpful to their goals. I am always pleased (and somewhat relieved) when athletes enter our store with a list of specific items from their coaches that are a part of their training and racing strategy.

6. Coaching goes beyond assigning workouts and strategy. Here is where coaching moves from science into the realm of art. Beyond knowing the basics of sport science and having a passion for helping athletes reach their goals, the most valuable skill a coach can have is the ability to “breathe” the athlete and effectively communicate with him/her. What does it mean to breathe the athlete? This phrase I picked up courtesy of Coach Ahmed Zaher, and it means getting inside the athlete’s head and seeing the world and their experience of the sport the way that he or she sees it.

Breathing the athlete is a skill to be developed. Some coaches come by it naturally, though there is always room for improvement. Coaches who tend towards empathy in general will have an easier time with this. Coaches - practice empathy, especially with individuals who you do not naturally “click” with. It will make you a better coach, especially if you learn to combine it with objective analysis. When a coach is breathing the athlete, he or she will be more likely to assign workouts and strategies that are both possible and sustainable for the individual, and will also communicate the goals of these sessions and approaches more effectively. Effective communication goes hand in hand with breathing the athlete. Another recommendation for coaches is to practice anticipated athlete conversations in advance to determine the effectiveness of your communication approach. Oftentimes, if you know the athlete well, you can identify conversational challenges in advance simply by having the conversation prior in your own mind.

7. Coaching provides not just a physical, but a mental strategy. Part of breathing the athlete is identifying mental and emotional limiters, and ways to address them if they are going to keep the athlete from his or her goal, or from having a sustainable experience in the sport. “Mental toughness” and “grit” are key phrases we hear in the sport today, but how do we develop these aspects? Part of coaching is providing the athlete with the necessary tools (such as positive self-talk, visualization, etc.) to develop these skills as needed. This is potentially one of the most difficult aspects of coaching, as it can look very different for different athletes.

8. Finally, coaching provides a relationship. Humans in generally are driven and supported by relationships. Good coaching creates a relationship that drives both the athlete and the coach. Endurance training comes with many ups and downs, and a trusting and positive relationship can carry individuals through the downs, and make the ups more rewarding, as they are shared with someone who fully understands and appreciates the work that was done.

I firmly believe (and have often seen during my own years in the industry) that an intelligent coach with less experience who is passionate, hard-working, has access to knowledgeable mentors/resources and is actively investing in a healthy, professional relationship with his or her athletes can be almost effective as (if not more effective than) a more educated/experienced coach simply because he or she will not stop in the pursuit of understanding how best to help those athletes achieve their goals.

One note for specifically coaches on a primary challenge of developing these relationships. Ultimately – this is why we do what we do. There is no greater feeling than watching your athlete cross the finish line as he/she achieves the “big goal,” and knowing you were an integral part of that journey. However, when a coach becomes deeply invested in an athlete’s development and success, it can be very difficult if/when that relationship is ended. This means finding a sustainable way to invest in your athletes, without giving more of yourself than you can continue to give to your athletes as the years go on. The relationship component of coaching is key, and giving too much initially can ultimately lead to burnout in the long run, which will negatively impact your future athletes. Invest wisely.

A final note – all of this is merely one coach’s opinion. Coaching isn’t always pretty, and it is never perfect, but in my experience a healthy coach/athlete relationship, backed by knowledge and hard work, can lead ordinary humans to do extraordinary things. Most importantly, we learn to do these things in a way that is sustainable and enjoyable. Working with a coach should make you more confident and healthy, and it should keep the sport fun (especially for age groupers, but I suspect this idea can be applied to elites, too). So if you’ve considered coaching in the past, but never taken the plunge – perhaps 2018 is the year you sit down with a local coach and at least examine what it might look like. And to my fellow coaches – I hope that you will continue to learn and grow in your pursuit of excellence as athletes continue to trust you with your health and goals.